Commuters drive through high levels of air pollution in Chiang Mai on April 11, 2023. / AFP

During the election season last year, combatting PM2.5—tiny airborne particles that pose health risks when inhaled—was one of the most popular policy promises among major parties in Thailand. In January this year, the House of Representatives approved all seven versions of the Clean Air Bill submitted to the floor by different entities including the government coalition, the opposition and civil society. While there are multiple domestic factors that contribute to the increase in PM 2.5 nationwide, heat spots from neighboring countries such as Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia also play a role. What all versions of the legislation have in common is a call for strengthened international cooperation with neighboring countries in order to combat transboundary pollution. As the northern part of Thailand is now suffocating in toxic smog, a clear plan for such cooperation is yet to materialize.

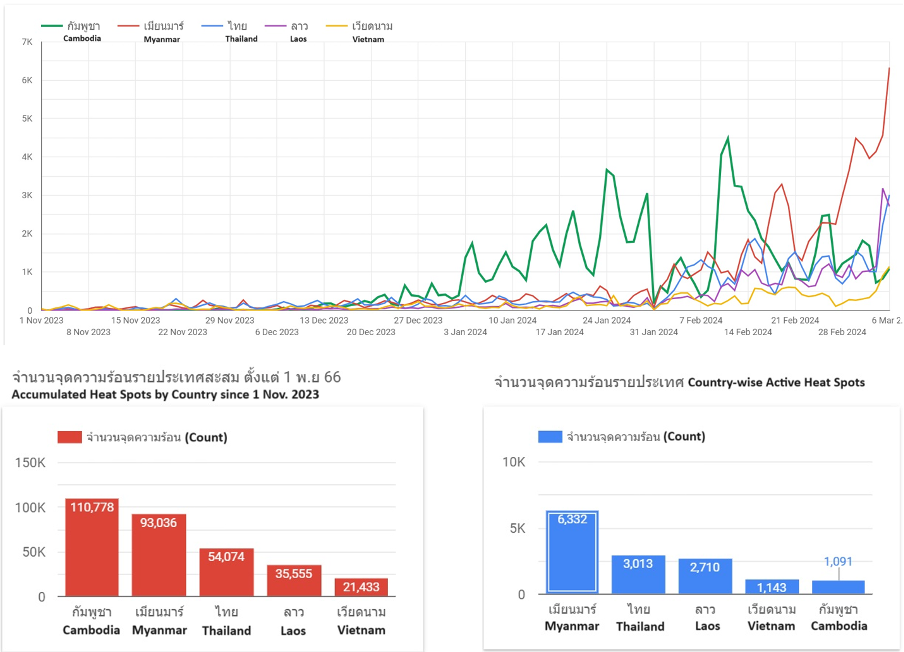

The data metrics of heat spots reported by GISTDA (Figure 1) show that while Cambodia has the highest count in terms of country-wise accumulated heat spots since November 2023, the country in which the heat spots are increasing most alarmingly is, in fact, Myanmar. At the time of writing, the country has over 6,000 active heat spots, ranking first among the CLMV countries. Back in 2023, a record-high PM2.5 level plagued northern Thailand for nearly four months, and the Thai ambassador to Myanmar reportedly discussed the issue with Myanmar’s minister of natural resources and environment conservation to raise Bangkok’s concerns over the problem. In response, the Myanmar minister simply expressed a willingness to expedite efforts to resolve the issue, but nothing concrete has been done so far. Throughout its tenure, the SAC (or State Administration Council, as the junta calls itself) has been ineffective, and perhaps even unwilling to collaborate with Thailand on transboundary issues—not only on the haze issue, but also the observable surges in drug trafficking, human trafficking, communicable diseases, and many other problems for which Thailand ends up having to handle the spillover unilaterally. Moreover, considering that the landscape of controlled areas has changed significantly in the past three years, this essay argues that it is unrealistic to seek any practical, government-to-government solutions from the consistently ineffective SAC. As the ethnic armed groups have managed to expand their controlled areas near the Thai border, replacing the SAC, it might be more viable to navigate possible engagements and collaboration with the ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) to tackle the transboundary haze problem.

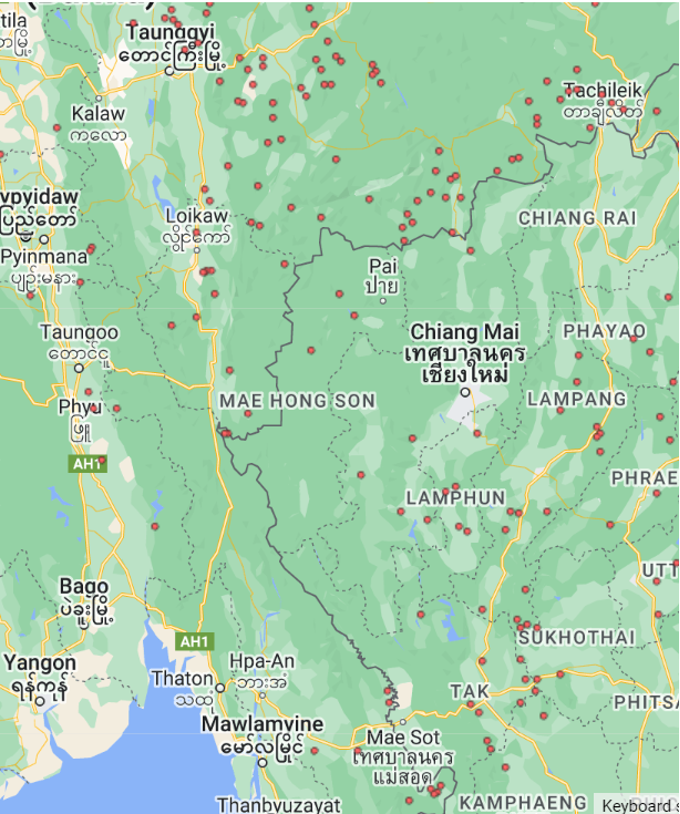

To illustrate this, the cropped map in Figure 2 below visualizes the active heat spots, focusing on the Thai-Myanmar border, since heat spots in this area are the ones that are likely to exacerbate pollution in Thailand. Overall, the heat spots seem to cover vast areas of Myanmar with some of them being very close to the Thai border, such as several in Shan State’s Tachileik (adjacent to Mae Sai, Chiang Rai); some in townships in Karenni State (adjacent to Mae Hong Son); and some in Myawaddy Township’s Shwe Ko Ko (adjacent to Mae Sot, Tak) and other townships in Karen State.

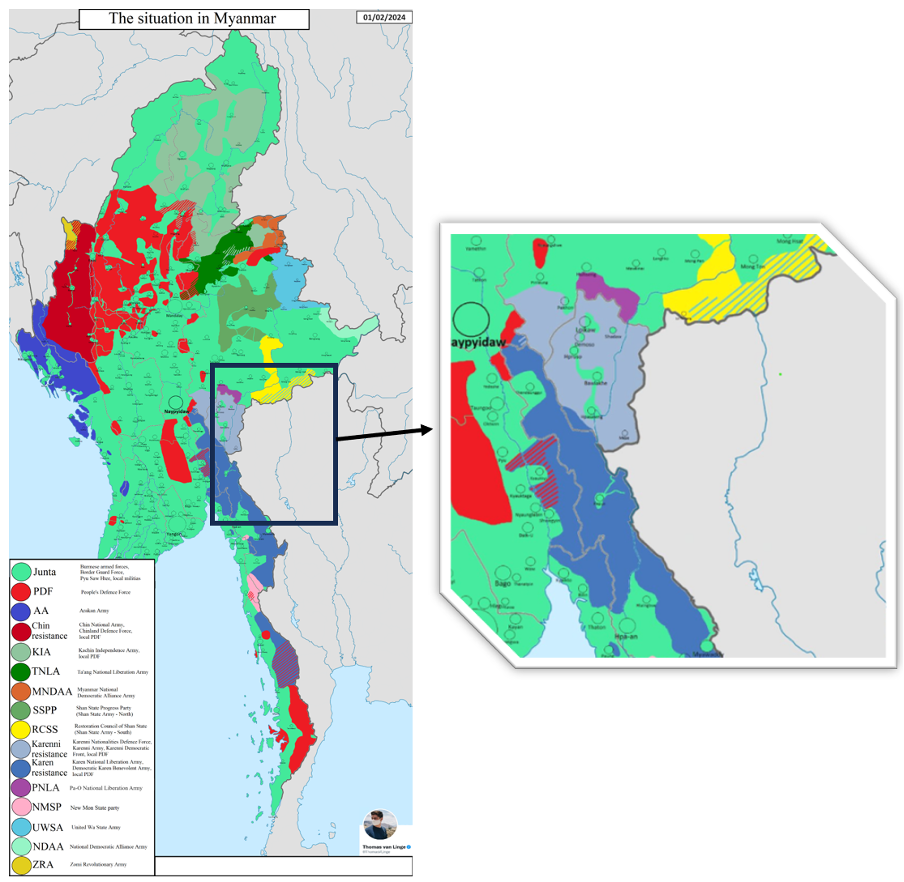

Simultaneously, Thomas van Linge, an independent journalist/researcher, posted a situation update map focusing on areas captured by key armed groups on his X (formerly Twitter) to mark the third anniversary of the coup this year. Figure 3 shows the full map with a cropped version to highlight the border areas, closely matching the map in Figure 2.

The two images clearly show that a potential solution for Thailand to alleviate the transboundary haze coming from a conflict-torn neighbor like Myanmar is to work more closely with the EAOs, since they are the ones controlling the border areas, not so much the SAC forces.

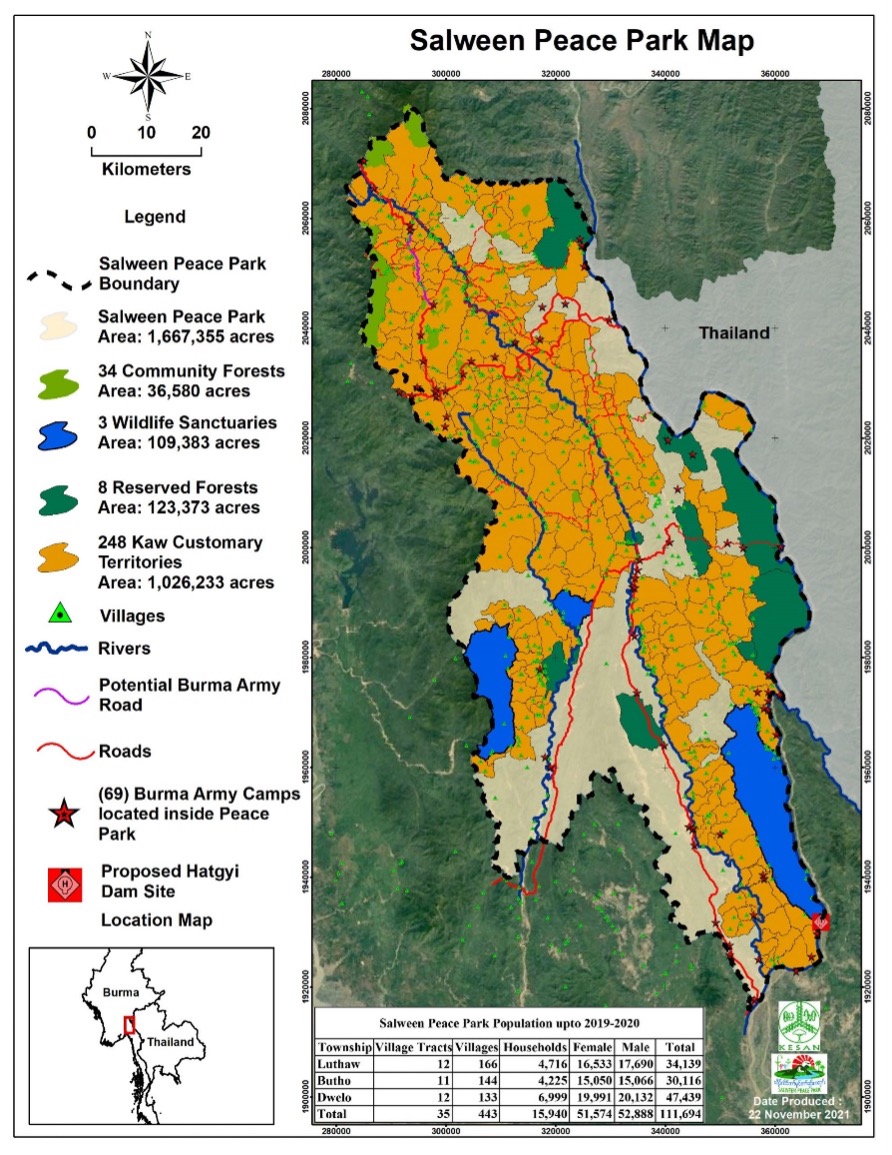

It is also imperative to note that some of these ethnic groups have developed an international award-winning climate action project from which Thailand has indirectly benefited through conservation of forest and biodiversity (Figure 4). In 2020, the UNDP awarded the Equator Prize to the Salween Peace Park Initiative (SPP) “for maintaining stability and conservation of a 5,400 square kilometre continuous ecosystem made up of protected areas, community forests and indigenous lands.” According to its website, the SPP is a community-led initiative that strives to empower local indigenous communities to revitalize their traditional practices, assert their rights, and manage their own natural resources. To that end, the Salween Peace Park Governing Committee was created to synchronize efforts between the Karen communities and the Karen National Union (KNU)’s Kawthoolei Forestry Department.

Given the joint forestry governance that the KNU and the Karen communities have developed to promote sustainable management in the case of the SPP, the knowledge and lessons learned from this initiative could even be used to develop Thailand’s own policy on climate change and to promote a collaboration between the local Thai administration and the Salween Peace Park Governing Committee.

Finally, in order to develop a sustainable and comprehensive solution to transboundary haze coming from Myanmar to Thailand, some of the recommendations in Ashley South’s book Conflict Complexity and Climate Change should also be considered. Given the presence of some post-coup political/administrative entities along the border, especially those in Karen and Karenni states, Thailand should practically readjust its approach to identify potential and realistic counterparts on transboundary issues, including haze management—especially when Thailand has a diverse set of capacities to provide and coordinate technical and financial support to the relevant environmental and climate change governance actors who are developing mechanisms in the ethnic-controlled areas.

Surachanee Sriyai is a lecturer and digital governance track lead at the School of Public Policy, Chiang Mai University. Her research interests include digital politics, political communication, comparative politics, and democratization.

Surachanee Sriyai

Dr Surachanee Sriyai is a Visiting Fellow with the Media, Technology and Society Programme at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. She is also the interim director of the Center for Sustainable Humanitarian Action with Displaced Ethnic Communities (SHADE) under the Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development (RCSD), Chiang Mai University